David Boyle (1958-2025)

David Boyle (1958-2025)

A tribute to David Boyle, Radix’s co-founder and former Policy Director, who died suddenly in June 2025.

Without David, Radix would not be Radix.

By Lesley Yarranton:

By Lesley Yarranton:

Poet and chronicler….David Boyle, my lifelong friend, publisher and co-author will be forever missed by everyone whose life he touched. I first met him nearly fifty years ago when we were both young newspaper trainees on a train headed to Harlow for a journalism training course. We shared the same eager curiosity about the world and its politics, love of words and horrified dismay at the severity of the brutal concrete ‘new town’ architecture that greeted us at our destination.

Since that day, few weeks would pass without a reading gift of some kind from him tumbling through my letter box, wherever I was in the world. Sometimes they were his own works spilling ideas harvested in his unceasing quest for the unravelment of things, other times works by authors whose ideas he generously wanted to share with me. These would be interspersed with unexpected, scrawled postcards from a trip I didn’t know he was making to some obscure European town to retrace the steps of a medieval king or unknown historical hero. And, always when we met, there would be no goodbye without homage to the historical or spiritual significance of the ground we were standing on, however modern and unremarkable it might appear.

His core philosophy that there is ‘hope’ in all things, if only you know where to look for it is a conviction threaded through the more than 70 books he published, ranging from What is New Economics? to How to be English.

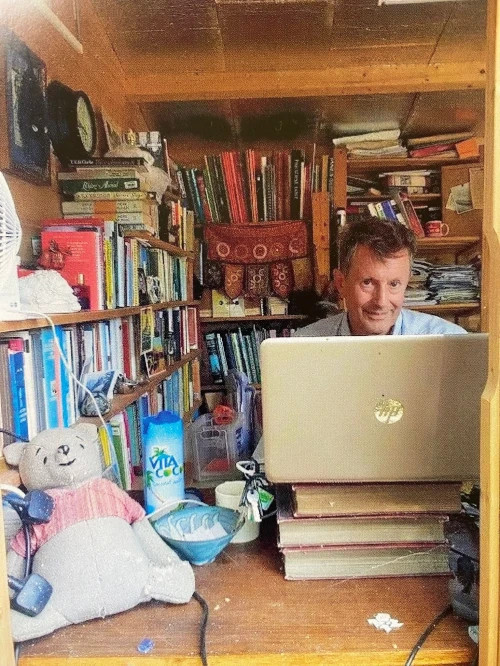

He had the ability to weave a lyrical undertow into the driest of council reports and transform indigestible chunks of dull analysis into sparking prose. He, himself, heaved with ideas and was willing to share them with anyone who would read or listen. Each one bore his trademark diffidence and humility – or even came wrapped in an apology for his having thought them up. He almost begs the reader of his ‘Oh, Shenandoah! book of ‘very selected poems’ not to think of him as the ‘somewhat obsessive type revealed in these pages.’

He taught me valuable life lessons such as never to be so certain about anything that it made you cross with anyone who disagreed. Mainly, he argued, because other people’s views were all so interesting.

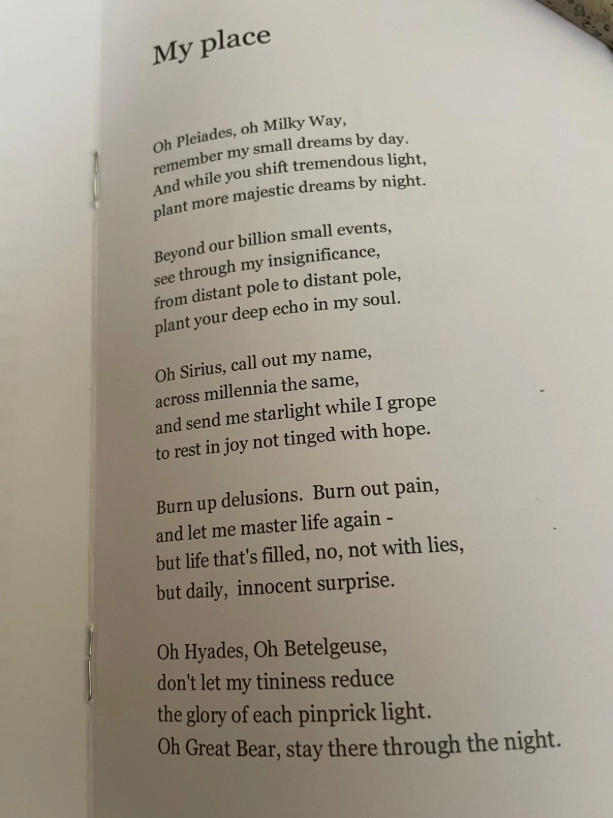

In this way, I feel, his life was filled ‘not with lies’, but with the ‘daily innocent surprise’ he spoke of in one of his finest poems, My Place. Yet despite such expansiveness, his mind remained a great mystery to me.

In this way, I feel, his life was filled ‘not with lies’, but with the ‘daily innocent surprise’ he spoke of in one of his finest poems, My Place. Yet despite such expansiveness, his mind remained a great mystery to me.

He was his own curious mixture of contradictions: A free thinker with many deep-rooted traditional beliefs, a campaigner, who refused to be partisan, someone who insisted on always showing compassion but was willing to spare nothing when calling out injustices.

He fought tirelessly against what he felt to be the growing unreasonableness of modern life, whilst not being immune to a certain singular strain of unreasonableness of his own, often to the confoundment of those closest to him. ‘What! You mean you don’t serve Earl Grey tea and scones here?! (to a waiter in a Japanese restaurant)…..’The important thing is to stand as a candidate in an election – the winning bit isn’t important at all!’ And, on one of my visits to his London home on a freezing December evening: ‘Turn the heating on? I’ve never needed to install any - I’ve got a piano’.

His determination to battle life’s injustices – not simply accept them – was called into action around five years ago when he found himself struggling to firefight a cruel form of Parkinson’s Disease that attacked his vocal chords reducing his rich, expressive voice to the barest of whispers.

After endless falls and wobbles, he resorted to wearing a cycle helmet, arm and knee-pads (we joked that it was like taking tea with someone in a suit of armour) and carried cheerfully and uncomplainingly on, patiently forever retracing his steps to search for the walking stick left behind. Take a look in the corner of the next bookshop you visit for there will be one of the walking sticks he absent-mindedly littered across London, wherever he went.

Even the necessity to offset the stiffness in his legs caused by medication was seized upon as an opportunity, prompting him to found a ‘gentlemens’ walking club’ of retired friends, who could accompany him on his increasingly wobbly ambles along the edges of the South Downs.

I feared a crack had appeared in his indomitable spirit after a shudderingly close-call with a tube train when he was toppled backwards by his weighty backpack. Overwhelmed by offers of help from passers-by, he muttered something about how he felt he must have appeared ‘ridiculous’ to people.

But a day later he was back at work, taking on the challenge of editing a book in a language he didn’t even speak – a task few would be brave enough to accept – and pulling off a final last great publishing coup with it. The day before he died he was drawing up plans as to how we would travel to Berlin to present it to the German media and, possibly, even take in a river cruise along the Rhine.

Bereft at his loss, we have to remember that he leaves us kindnesses and ‘word gifts’ enough. But I, for one, will forever defy the command given in his poem, Dark, not to mourn the ‘loss of bright.’